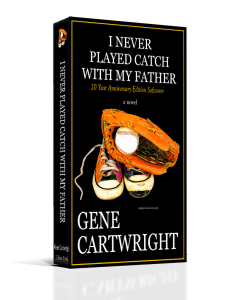

ISBN : 978-0-9649756-7-5 – 6 x 9

20th Anniversary Edition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

When I Never Played Catch With My Father was first published, in hardcover in 1996, the World Trade Center served as the setting for the business office headquarters for the main character. In light of September 11, 2001, we considered editing the manuscript to reflect a different location. However, we decided to maintain the integrity of the original manuscript, leaving the setting as it was intended. We honor those Americans who lost their lives on that day, and are sensitive to all that thereto pertains.

Our thanks again to Oprah, who after reading this novel, invited Gene to be a guest on The Oprah Show. This novel has been called one of the most loved baseball books written. But this story is about so much more than sports. You will see that in this novel, sports is a metaphor for real life.

Today, the publisher has decided to include significant portions of the early chapters in my blog. To read and learn more, and to add this book that celebrates its 20th year, please see GeneCartwright.com, where all print books include a free eBook in any format.

Enjoy.

_________________

One

I Remember ____________________________

“Dear God, I am only seven, but I have already decided what I am going to be, and what I am not going to be. The rest is up to you and me, but mostly you.”

On the day I turned seven, my world became a different place. Instead of making wishes and blowing out candles, I closed my eyes and made two solemn vows. One was to someday become a major league baseball player; the other was to never be poor. Even then, I knew have was better than have not. While my first vow was the stuff of every boy’s dream, my second was born of a tragedy I still wish I could forget.

During the night before, a transient family, apparently seeking shelter, trespassed onto the abandoned Devereaux farm, about four miles from ours. In the early morning hours, an oil lamp fire raced through the dilapidated structure burning it to its frame. Everyone inside perished in the raging inferno. Authorities reported finding the charred remains of a man, woman, and three children huddled inside, only five feet from the front door. They came so close to getting out. Tragically, it appeared thick, choking smoke obscured the main escape route and overtook them.

The stunning news was delivered to us by a neighbor, Mr. Jules Stimpe, about 8am that morning. Our family of five had just finished downing a Texas-sized, country breakfast of ham, eggs, grits, hash browns and homemade biscuits. I was looking forward to later opening gifts, blowing out candles and stuffing myself on five-layer, double chocolate birthday cake.

Normally, we Phalen kids would have been ushered from the room, before grownups began serious talking. But everything happened so quickly. An emotional Mr. Stimpe, winded and wild-eyed, blurted out the jarring words, the minute he bolted through the front door.

“Y’all heard, yet?” He yelled out. “Y’all heard?”

We all gazed at each other with wonderment. None of us had any idea what he was squawking about. Before anyone could ask what he meant, Mr. Stimpe continued apace, gesturing frantically. His plate glass-thick eyeglasses tumbled from his bearded face, saved only by his ample midsection. He seemed about to burst with whatever it was he was trying to say.

“The ol’ Devereaux place caught fire, last night!” He said. “Five people burned up inside the main house; man, woman, three kids, they think. Hard to tell. God help ‘em.” His voice cracked. “Oh, my god!”

Mother shrieked, thrusting both hands to her flushed face. That did not slow Mr. Stimpe one bit. He kept right on going, nonstop.

“Poor folks didn’t have a chance in the world. Probably just put up there for the night, I reckon. No ‘lectric or nothing up there. They think an ‘ol oil lamp was the cause of it. Likely found it in the barn. Used it to eat by and all,” he said.

My heart leaped to my throat. I felt it thumping so fast it scared me. I knew what I had heard, but it just…it just did not seem real to me. It was so incredible. What added to the weight of the moment was Mr. Stimpe himself. Here was a somber man—a church elder and all—normally so slow and deliberate, he was the butt of jokes amongst some of us kids. We called him Mr. Mo, short for molasses. Now here he was pacing in our living room, tripping over his words and waving his arms around.

“You saying they all dead? You know that for sure?” Father asked, hoping there was some mistake. He drew to within inches of his friend.

“There is no mistake, J.Q.,” said Mr. Stimpe. “I wish there was. God knows I wish there was.”

A long, pained silence followed. “Think they were anybody we know—anybody from around here?” Father asked. Mr. Stimpe shook his head several times.

“No, don’t think they was from roun’ these parts. From what I hear, an ol’ beat up car with Okie plates was found parked outside.”

I knew father frowned upon use of the term, Okie. He sighed a bit, but let it ride this time. This heart-wrenching news had our rapt attention. We were all struck dumb by it. Seeing mother so emotionally overwrought brought tears to my own eyes. I had never seen her this way. I did not know what to think.

Mr. Stimpe rambled on. Father kept trying to get him to slow down; had him take a deep breath, repeat everything more slowly. It was only after he had stopped to take the much-needed breath, that mother noted we were still in the room. By then, it was too late to have us leave. We had heard everything.

I am not sure when I found my voice or was able to stir from where I stood. I do know I instantly lost my appetite and could not eat at all the rest of the day. Mother just stood there in the middle of the living room. I can still see her, especially her eyes. Tears streamed down her face. She shook her head from side to side, mumbling something I could not quite make out. Whatever it was, she kept saying it over and over again—some mournful mantra, as I recall.

I found it impossible to even imagine the terrible thing we had heard described. My big brother, Carter, and I wondered aloud how something so awful could happen to real people. I trembled, just thinking how much this poor family, especially the children, must have suffered. Carter and my sister, Rosie, both older and slightly more composed, tried to comfort me as best they could. Truth is, we were all awash in tears.

As soon as Mr. Stimpe left, a somber father summoned us all into the living room. Neither he nor mother thought it necessary, or had the presence of mind to explain to us the horror we had just learned about. I had so many questions, but held them inside. I was not sure I fully understood the reality of human death. Of course, I had seen dead farm animals, but I had never seen anyone cry over them.

Father stood near the large bay window and read several scriptures. Moments later, we all prayed for the deceased family. We did not know them, but that did not matter. Afterwards, mother gave us all especially long and powerful hugs. Her salty tears fell on my upturned face. I remember her chest heaved with every sob, while she held us close to her. She seemed reluctant to let go.

Father did not say much. After praying, he strode out onto the long front porch, lingered there for a time, gazing in the direction of the Devereaux place. I quickly followed and stood a couple of steps behind him, shrouded in his shadow. I recall seeing a dark, smoky haze in the distance and remember the acrid smell of smoke that hung heavy in the morning air. Aware of my presence, father turned to me and noted my pained expression.

“Go on back inside, son,” he said. “Go on.”

“Can I stay here with you?” I asked.

“Got things to do directly,” he said. “Stay here with your mother. I’ll have some of your birthday cake, when I get back. Go on, now.”

“Where you going?”

“Can’t go with me this time, son.”

“How come?” I asked him. “I won’t get in the way.”

Father gazed down at me, tousled my hair with his right hand and again insisted I go back inside. That was not what I wanted to hear. I felt so safe, standing next to him, hearing the rumble of his deep voice, feeling the protection of his towering presence. I did not want to leave his side.

A half hour later, Mr. Noah Peetson, another neighbor and a reserve deputy sheriff, pulled up in his prized, black Packard automobile and honked twice. I was not at all happy to see him. I even tried to wish him away, without success. Father soon left with him, after whispering something to mother and planting a gentle kiss on her forehead. I assumed he and Mr. Peetson were headed to the Devereaux place, to see the destruction for themselves.

Moments later, a strangling, suffocating feeling engulfed me. I could not stand being inside the house. My breathing became labored; beads of prickly sweat covered my brow. It seemed the four walls were closing in on me. Carter must have noticed my distress. He turned toward me, caught my eye and nodded for me to follow him. I did.

The two of us hurried through our rambling ranch-style house and onto the back porch. We bounded down the steps and struck out across rolling, green fields, toward the towering ‘Man O’ War’ oak tree, on top of Heritage Hill. That is where we always went, when no place else seemed big enough.

There was a very personal reason for the depth of my sadness. Purely by chance, I had seen that family the day before, while in town with father. They were riding in a clanking, smoking, 1954 Desoto bearing Oklahoma license plates. The old car was the only family possession to survive the flames, unscathed.

I recalled the soiled faces of three children: two girls and a boy, peering out of the car at ogling townspeople, including me. We glared back at them, as they chugged through town. The young boy appeared to be about my age. He seemed saddest of all. In spite of only a fleeting glimpse, there was something about his eyes that struck me; they were distant, yet piercing. His stiletto gaze seemed to slice right through me. My connection with him was instant and eternal.

I stood in front of Stoddard’s Five & Dime, staring, as they limped out of town. Nauseating smoke spewed from the rickety old car’s dangling exhausts. It made a god-awful noise, drawing derisive laughter from some. I was sure they did not feel welcome to stop. If only I had smiled, I later thought, or given a friendly wave.

Carter and I reached the old oak and stood there in stony silence. There was little need for words. I wondered about the boy. What was his name? What kind of life had he lived? Did he like chocolate cake? Did he have friends—great friends like mine? Of course, no one else could possibly have had friends quite like Duncan Stoddard, Peetie Simpson, Jed Stimpe, Iggy Davenport, Twenty-one Smith, and the rest of the guys.

Had this boy ever gone fishing, jumped logs, skipped rocks, picked wild berries in summer, or played baseball? I prayed he had at least experienced the latter. It would have been a shame to die never having played baseball.

For months thereafter, my nights were filled with recurring dreams, not nightmares, but dreams filled with images of this family. In those dreams, everything always turned out differently. Everyone survived. They were all able to escape the flames, scramble into their old car and flee to our farm.

In my dream, we took them into our home, fed them, gave them new clothing. After a few weeks, with their old car repaired, the family left for Dallas, where the father had been offered a job. The day they left, the boy and I exchanged baseball gloves and promised to stay in touch. Then, I would always awaken, just as they were driving away. I would sit up with a start and realize it was all a dream. That always saddened me, because I wanted it to be real, not some silly dream.

One night in particular, I awoke to find mother standing by my bed gazing down at me. Apparently, my fitful sleeping and my crying out during the dream had awakened her.

“What’s wrong, James? What’s wrong?” I remember her asking.

Surprised to see her standing there, I did not answer right away. Mother moved closer. Coaxing me from bed and taking me by my hand, she led me into the kitchen. There, she poured me a glass of milk then sat stroking my face and watching me drink.

“It’s the fire, isn’t it,” she said. I glanced up quickly. She knew. I had not told anyone about how I felt, but somehow she knew.

“Yes,” I whispered. “Yes.”

“I figured as much. You haven’t been the same, since all this happened. You haven’t been my same little baby boy,” mother said. “I am not a baby, mom,” I protested mildly.

“You will always be my baby,” she said, smiling. “But I have a feeling there is more to all this—more than the fire. Listen son, you can tell me anything. Mother understands. And it’s alright to feel whatever it is you’re feeling inside. I’m sad too. We all are. I want you to know you can tell me whatever is troubling you. Don’t hold it inside.”

I insisted there was nothing more, but mother knew better. Call it intuition or whatever, but she had a sixth sense when it came to things like that. Finally, with her gentle insistence, I told her all about seeing the family in town the day before they died. I told her about my dreams and we both cried. Mother put her arms around me and assured me I had nothing to feel guilty about; that I was in no way responsible for the insensitive actions of stupid adults.

A half hour later, I was much calmer. I even finished the milk, except for a swallow or two. I could never drink a full glass of anything, even to this day. Just as we were about to leave the kitchen, we heard father stirring. I jumped to my feet and wiped my eyes.

“Mom, please don’t tell father about any of this. You have to promise,” I said. “You have to.”

“Why, son?” She asked. I swallowed hard, trying to think of some way to avoid answering. Mother waited patiently, pinning me with her gaze.

“I don’t want father to know I was crying about it. I don’t want him to think I’m still a kid, ‘cause I’m not. I’m seven, now. I’ll be a man, soon. And men don’t cry like children. Daddy never cries. Only babies and sissies cry.”

Mother appeared stunned, taken aback by my wordy response. I even surprised myself. She gripped my hand, stared into my eyes. Before she could say anything, I darted for my room as fast as I could. The subject never came up again.

To this day, thirty-five years later, the vivid memory of July 6, 1960 haunts me. Every single birthday I have had since has reminded me of that fateful morning. Saddest of all, no one ever claimed the remains or reported such a family missing. Dental records were never located. How was it possible a family of five could perish and not be missed by someone? It was as if they never existed.

Three weeks later, it was discovered the car they were driving had been abandoned a year earlier by its Tulsa owner. Exactly one month after the fire, all were buried together in a single, Crawford County, pauper’s grave. Father read a brief passage of scripture. Elder Johannsen prayed. Mother and Mrs. Stimpe placed flowers next to the simple marker, which read: A FAMILY THAT LIVED AND DIED TOGETHER. JULY 6, 1960

So, even as I celebrated my seventh birthday, grieved and shed tears for members of a family whose names I never knew, I made my two vows. In spite of my youth, it was clear to me, had this family not been poor and homeless, their fate would likely have been much different. They would not have been at the old Devereaux place.

As traumatic as this experience was for me, it was atypical of the normally predictable, carefree, storybook realities of my small town life. I suppose that is why it made such an indelible impression upon me. I felt forever bound to this family. And it was by no means the only tragedy I credit with altering my view of life.

In 1994, while I sat in my World Trade Center offices, a stunning event, which I will detail later, cemented a decision that altered the course of my life. The winding path leading me to that pivotal decision was fraught with numerous twists and turns. Many events combined to force me to face the truth about my past and myself. I had no idea such a journey lay before me.

To explain it all, I have to go back to those innocent, memory-filled days spent as a child. I often wonder how I got here? How did New York City become my home, my throne-room, my gulag? Before I answer these and other questions, there are many things you should know about me.

For an impressionable seven year-old, the horror at the old Devereaux farm presented a powerful lesson in life and death. For the first time, I realized just how fortunate I was. I even looked at Carter and Rosie in a more endearing way. The experience also foisted upon me an awareness of the terrible effects poverty can have on the life-choices the poor are forced to make.

I began wondering how and who decides to whom one is born. Who determines which of us begins life rich or poor, healthy or infirmed? It all seemed such a toss of the dice. I could have been that boy. I could have been any boy—even a girl, for godsakes. I could have had entirely different parents. Only I would not have known I was someone else. That was the jumbled way I thought about it, then.

In my small, north-central Texas hometown of Rosedale, I saw the pity and scorn some heaped upon poor people. I witnessed their piteous struggle for esteem. They always seemed so…so sad, so isolated, even shunned. I also learned of the poverty suffered more than a generation earlier by my own family. I wanted no part of it.

With divine intervention, I have at least kept one of those vows made thirty-five years ago, long before experiencing the onslaught of fame, fortune, and heady publicity. My journey to success has been an amazing ride. I have basked in the notoriety; the celebrity status; the peer praise; but enough is enough. I am no longer flattered being constantly referred I Never Played Catch With My Father 23 to as one of America’s wealthiest men, although it is true. I now cringe at the very sound of those words.

So, I will state for the record, I am a rich man—a very rich man able to satisfy virtually any material desire. Being a humble farm boy, from rural Texas, I cannot describe the feeling of awe, and the sense of responsibility, the realization inflicts upon me. I do not overstate, when I say this success has exacted a significant price, as you will learn.

Despite the temptation these days for the media to reduce every issue to sound bites, every public figure to simplistic caricature, there is more to me than the numbers used to define me and quantify my wealth.

In 1993, President Clinton named me, and a dozen others to a panel invited to the White House to discuss budget and economic issues. My first inclination was to decline the invitation. I did not relish the possibility of being drawn into partisan politics. However, I reluctantly agreed. After all, it is not every day that one gets a personal call from the President.

Shortly after arriving in Washington, D.C., my worst fears were realized. The moment I stepped into the Rose Garden, following our initial meeting, I was singled out for pummeling by the press. Amongst other things, they were bent on determining my party affiliation and my personal appraisal of the President’s economic policies. One reporter even asked my views regarding Whitewater. I simply ignored him and recognized another eager inquisitor.

I was further bombarded with unrelenting questions about my personal wealth, not my ideas regarding the nation’s economy.

“Mr. Phalen, is it true you recently made 800 million dollars in a single day, as the result of an international currency transaction? And how much do you give to charity, annually?”

“Mr. Phalen, has the President or his people approached you to contribute to his legal defense fund? And do you think he’s been candid in response to the various allegations?”

“Mr. Phalen, how much did you pay in taxes last year and may we see your personal returns?”

I was aghast. It was truly amazing to witness. How anyone can survive in such a shark-infested environment is beyond my understanding. I have no plans to show my face in Washington again anytime soon. I do not need it. You have to be a masochist, a lobbyist, a journalist, or a special prosecutor to survive in such an environment.

I have been fortunate to have a few great friends who help keep me humble and anchored to reality. With even the most modest of egos, it is sometimes difficult to not be personally affected by all the hype regarding one’s own brilliance and well-doing. These are friends not impressed by my social standing or balance sheet. They can be and usually are brutally frank.

On a cold December 22 last year, I experienced lunch at the New York Ritz-Carlton, with just such a friend, Miss Melody Ann Melford—a remarkable woman. We met five years earlier, when her red Jaguar she was driving clipped the rear bumper of my vehicle. Unfortunately, we were both trying to exit the driveway of the Ritz at the same time. She was ninety-eight then, but exhibited the energy of a spirited sixty year-old.

Miss Melody exited her car, wearing a blue, designer business suit, and approached the limo so quickly I hardly had time to get out. She assured me this was the first auto accident she had ever had and did not want to blemish her perfect driving record. Standing less than a foot from me, and staring into my eyes, she said if I was as nice as I was handsome, I would not call the police. What could I do? She was so charming and apologetic I was totally disarmed.

The memorable incident gave birth to a very warm and lasting friendship. I only wish I had met her years earlier. Sadly, Miss Melody died three weeks ago, at the tender age of 103. Her charm, her feistiness, her quick wit had no equal. She had doleful eyes that twinkled, possessed a knockdown sense of humor, and had chutzpah to spare.

During last year’s lunch, I recall asking Miss Mel to what she attributed her long life, her youthful spirit, and her boundless energy. She did not miss a beat.

“Several things,” she said with an elfish grin, easing her fingers through her elegant white hair and leaning closer to me. “For one thing, I never eat, drink or put anything into my body that I wouldn’t give a 10 year old. That’s one of the reasons I still have my own teeth,” she boasted proudly.

“What about your occasional glass of wine?” I asked, displaying a wide grin and a “gotcha” look on my face.

“Mind your own business, Phalen,” she said with a wink and feigned punch, “My wine is purely medicinal.” I had no choice but to agree. “Second, I never worry about money at all,” she said. “Never wanted so much of it as to have to stay awake nights trying to figure out how to keep it. And I have never lost the child in me. If the child in you ever dies, you are already dead as a doornail. It just takes a while for them to bury you.”

That is what I meant by experiencing lunch with Miss Melody. She was a captivating spirit, a tireless spinner of tales, and a self-described admirer of healthy young men. And although she had buried three husbands, she insisted on being called Miss.

Miss Melody declared each husband was special. However, her one complaint was that she was yet to find a man who could match her IQ, creativity, and physical stamina. The latter she boasted with a sly wink and naughty smile. I did not ask what she meant. I feared she would tell me.

Miss Melody’s views about money and the way it colors life, forced me to think seriously about my own rewarding, yet often harried existence. Do not misunderstand; I never considered taking a vow of poverty. I simply reflected upon her passionately held views. It was impossible to ignore anything she said, especially when she clutched your hand, leaned into your face and shook her finger at you.

Some mornings, I lie awake in the master bedroom of my Park Avenue apartment, gaze up at the muraled, ten-foot ceiling, and wonder if I have been fantasizing about my success. I say success because I draw a clear distinction between success and wealth. I believe one can be successful and not be especially wealthy. However, I am blessed to be both.

Do not be put off by my candor. I am no braggart. To the contrary, I am humbled, just being able to honestly make such statements. When I was eight or nine years old, father read a passage of the bible to me that said: “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven.”

After hearing this, I wondered just what was so wrong—so inherently evil about wealth. Should I not aspire to be rich, so my odds of entering through the Pearly Gates would not be diminished? Was I to understand the only virtuous people were the poor, who somehow tended to lead more righteous and circumspect lives? I think not. The more I have lived and observed many peoples, the more I have come to see that sin and evil are not exclusive to the privileged class.

I now understand the passage father quoted suggests the rich tend to have more faith in themselves and their money, and less in the Almighty. Father said they preferred having their heaven here and now, rather than in some sweet bye and bye. I concluded if that were true, then poor people must be suffering their hell here on earth, and therefore inclined to believe their heaven would come later—a deferred plan of sorts.

Regarding my own wealth, while I am not exactly a Bill Gates or a Warren Buffett, if I never earn another dime and happen to live a thousand years, my lifestyle would not suffer. I realize I am living an incredible dream afforded few.

Notwithstanding all this, I remain astonished at the wealth existing in this country. I marvel at the opportunities to accumulate great wealth for those, who either by circumstance of birth, good fortune or dint of will, get to play the game. And believe me, the frenetic drive for success and fortune can be a deadly, high-stakes game—a war, with battlefields strewn with casualties.

For me, getting into the game certainly was not due to the circumstances of my birth, unless you count the limitless love I inherited, and I do. All I have is a product of great luck, very hard work, a fearless spirit, and my reliance on faith infused in me by my parents. I confess this reliance on faith has tended to both soar and crash over these years, yet it remains an integral part of my life.

Still, I often ask: “Why me? Why have I been so fortunate? Why not the homeless people standing on street corners begging for spare change? Why not millions of others who are smart, work hard, pay their taxes and barely make ends meet?”

Again, I do not mention my wealth to boast. So please do not think me lacking in modesty; there is a point to my belaboring the fact. I know there are extremes of wealth and poverty still existing in America. I do much to help those who are less fortunate. Because of the values my parents instilled in me, I feel a deep sense of responsibility to be a good steward of all I possess.

Yet, in one significant respect, I too am a poor man. I say that, because despite my finances, despite the honors, the peer praise, the ego stroking, and things used to keep score, I cannot purchase at any price the one experience lacking in my otherwise enviable childhood—a I Never Played Catch With My Father 27 playful moment with my father. I cannot recall a single one. And believe me, I have tried, stopping just short of inventing such a recollection.

This may strike you as odd, perhaps incredulous, but for such a moment, I would gladly pay a million, a hundred million dollars. I would pay any amount. After all, what value should one place on such priceless memories, which I believe help form the foundation of genuine happiness? I can always make more money.

Still, I am only a man—a mere mortal. And like you, I am unable to capture lost moments or alter the past in any way. I wish I could. I have to laugh when I hear some call me powerful. I am not taken in by that hackneyed characterization. By powerful, they simply mean I am filthy rich. I detest the moniker. It suggests I am who I am, solely because of limitless financial resources that alone grant me this so-called power.

Filthy rich or powerful or not, it is regarding the absence of certain childhood memories that my perceived power fails me. All my influence, all my successes, all my ability to control people and events do not matter one whit. I cannot summon to mind memories of events that never occurred. I cannot rewrite the history of my childhood, to fill in the missing pages with moments I only wish I had known. I cannot turn back the clock and change the fact that…I never played catch with my father.

Even as I write these words, I find myself wishing the truth were different. Unhappily, it is not. Although baseball was my all-consuming childhood passion, I never experienced the joy of sharing it with father. It is surprising, but of all the things in my life that could matter to me, this seemingly insignificant fact most defines my disappointment, quantifies my poverty.

While I truly miss not experiencing this hallmark event with father, my regret goes far beyond not having tossed some ball back and forth with him. There is much more to it than that. The fact we never did typifies the absence of a deep heart and soul connection so vital to fathers and sons. Neither wealth nor success is a substitute. This bond is irreplaceable.

So, when people make erroneous assumptions about me, analyze me, probe my life, and wrongly conclude I have it all, they are wrong. What does having it all really mean anyway? Who ever really has it all?

When I was growing up, I frequently felt the sting of disappointment, whenever father chose to do more important things. At the time, I had no idea these and other fatherly absences and omissions would come to mean so much to me. I simply accepted the realities.

Kids seldom forget things that truly matter to them. If you are a parent, ask yourself which you would most regret in twenty years: missing another boring meeting or not witnessing the look of ecstasy on your kid’s face when he or she spots you at a school play or little league game?

Should I publish this book, I realize some will read the foregoing paragraphs and think: How dare this rich WASP complain about such trivial, personal matters, when countless poor kids are doomed to live in urban squalor never even knowing their fathers.

I understand the cynicism. However, all things are relative to individual circumstances. Of course, my own disappointments pale when compared to hunger, homelessness, Aids, and other regrettable human conditions. It is because of my own experiences and awareness of my blessings, that I spend money and time trying to improve the lives of kids and adults in New York and elsewhere.

I refuse to be branded with guilt for having enormous wealth. I make no apology for my success and reject personal responsibility for elevating all unfortunate souls. I recognize that like others, some wealthy people can be insensitive and disgusting. I have even met and on occasion associated with some of these people.

However, beating up on the rich seems to have evolved into some sort of blood sport in this country. I for one refuse to be a casualty. My broad-based philanthropy speaks for itself. Besides, I would much rather be my brother’s employer than my brother’s keeper. Forgive me for sounding my own siren. In some respects, I feel I am debating myself. That is not my intent. I am whom I am, as cliché as that sounds. The horror stories of others do not diminish my disappointment, regarding experiences many consider rights of passage.

It is no trivial matter to me. However, I am perplexed that at this stage of my life this still weighs so heavily upon me. Surely by now, all this would have long ago faded into the foggy domain of lesser things. Yet, it is seldom far from the surface. It evokes deep sadness; a feeling of eternal loss, not anger. I feel that loss, each time I see a father tossing a ball toward the outstretched hands of a young son eager to prove himself his dad’s equal.

Whenever I catch a game at Yankee Stadium, I nearly always spot a beaming father and his hotdog toting young son. They are often outfitted in Yankee caps, pinstripe jerseys, carrying gloves and determined to bag that elusive foul ball.

On the heels of an exciting play, the father leans over and explains what happened, in details that would put Vin Scully or Harry Carrey to shame. That is what I mean, when I refer to lasting memories that help form a solid foundation for life.

I sit there, my mind goes back, and I could not care less about the bulls and bears of Wall Street. A lump forms in my throat; my eyes grow moist and, for a time, I am no longer aware of what is happening on the field.

For a moment, I indulge myself. I imagine I am that young boy, that the man is my father, the moment belongs to us and the experience is ours to share for a lifetime. It is all quite real to me. And though I feel I am an intruder, I permit myself to bask in the warmth of that delusion for only a moment—a fleeting moment.

My name is James T. Phalen and I find myself at a crossroads. A perplexing change is enveloping my life and, frankly, I do not feel so damn powerful and in control. Where is all the invincibility others have attributed to me?

I have come to a time and a place in my life where the road longtraveled seems dark, twisted, even impassable. Certainty has become uncertainty. Supreme confidence threatens to succumb to debilitating doubt. This is not like me. This is not the world I know. Worst of all, is the feeling of not being in complete control.

This kind of affliction can strike anyone; rich, poor, black, white, brown—anyone. No one is immune. It is seldom something that happens abruptly. There are no lightning bolts, no big bangs, no earthquakes. It happens subtly. One day, everything seems to swirl around you, even as you are standing still.

Why is this happening to me? Perhaps all this introspection is a result of my being forty-plus, advancing through middle age, and facing questions of life and death. Perhaps.

One day, one awakens to find the old notions and familiar landmarks have somehow shifted, or disappeared altogether, and no one bothered to tell you. The old rules no longer serve to guide or direct. Long-held, once revered assumptions and perceptions of what is important, of what gives meaning to life are no longer enough.

When the mask that often adorns us all is stripped away, we are left naked—left to discover we have perhaps never really known ourselves, let alone anyone else. Such self-appraisal does not come easily. It can be scary.

Having wallowed for so long in a world of greed and self-fulfillment, I had grown to think myself immune to such emotional mumbo jumbo about time and place and roads long-traveled. It seemed a bit too esoteric for me. As long as I had my cell-phone, my fax machine, my computer, my Gulf Stream Jet, my motorcar, my money, my credit cards and myself, what else could I possibly require? You may say I was selfconsumed.

Forget all this New Age, self-god crap hyper-promoted by selfanointed gurus preaching auto-evaluation, while hawking fake crystals on home shopping networks. I was already focused inward. I did not need some spiritual imposter taking my money; in return for convincing me I was my own center.

I riveted my focus on the big, shiny, gold ring; forget brass. And when my goal was reached, my focus was fixed on the next one and the next one. I kept moving. One thing was certain; I would not die in place; no standing still and offering the grim reaper no challenge whatsoever.

Success became a fix, as addicting as heroin or crack, only without the social stigma. Indeed, our society celebrates and even demands such success. Failure (anything below first place) is not tolerated in America. If you doubt this, tell me where I can find all those monuments erected in adoration of General George Armstrong Custer’s silver medal-winning finish.

Now, to my wonder, I am at a crossroads I had not expected to reach so soon, if at all. It is a place where fame and fortune are not enough. I find this circumstance painful, sobering. At times, I feel stupid acknowledging my difficulty explaining or coping with this. After all, I have been socialized to believe and to act as if men can, and should be able, to deal with anything.

More and more, I find myself brooding about life and death, about this complex and brutal world around me, and my place in it. So, what if I Never Played Catch With My Father 31 I have amassed a trove of grownup toys, trinkets and treasure? A hundred years from now, who will know or even care that I was here? What positive contribution will I have made? Why should I care?

The intoxicating elixir of attaining enormous personal success, the adrenaline rush that comes from playing the ‘game’ well, seems unable to satisfy me as before. I feel an emptiness that grows daily. Why is this?

In the midst of my day-to-day madness, I long for simpler times and at day’s end am left with only my longing. More and more, I am drawn to lingering thoughts of my childhood, and those stilted, unresolved memories of father. But why has this surfaced now…why at all?

I am under no illusion. I am no writer—no professional writer. I have no intent of trying to pen a 700-page encyclopedia of my life. What follows is simply an open letter to me and to father, whose watchful gaze I still feel upon me. After all these years, I feel the undeniable urge to move beyond private thoughts and whispers, to speak aloud, even if only to me. I feel a need to empty my overflowing heart; something I have never taken the time to do before. It never seemed manly enough; not enough coarseness, danger, sweat, derring-do, grit, grime and Lava soap.

I have always felt that if I ever took the time to write, it would be about Wall Street. I would likely pen some exposé with sordid details of shameless acts committed by seedy characters with choirboy facades, thousand dollar suits, respectable titles, pricey European motorcars, and tastes for fine wine and women with first names only. However, here I am turning the probe inward. It is long overdue.

Look, I was not always the person I am today. I had a wonderful childhood, despite the few though lasting regrets. I had a life, long before this. I had joy and sadness, laughter and tears, just like you. Who I am now, both public and private, is a result of that life and that childhood.

While I would be happy, if this book strikes a resonant chord with millions of readers and makes me a best-selling author, that is not my primary goal. I would write this book even if I was the only person on earth.

If I am lucky, writing this book will help me resolve lingering questions about my childhood. Heaven knows I could use that, because I have been in denial regarding aspects of my past. I have long realized I held a view of father not clear or wholly endearing. To escape confronting these realities, I have maintained a state of perpetual motion, not permitting myself more than a moment to pause and reflect, until now.